Lascaux Cave Painting: The sophistication of pre-historic culture

- Rattlecap Writers

- Feb 24

- 4 min read

Written by Emily Martin

Illustrated by R. Fischbacher

The twenty-thousand-year-old art found in the Vezere valley in Dordogne, France is evidence of the outstanding display of the ancient human genius and artistic ability. With its calculated composition and use of three-dimensional space it provides an insight into the pre-historic Magdalenian culture of western Europe.

As a preface to the description of the cave art of Lascaux, some background on the prehistoric people of Magdalenian culture would be beneficial. The Magdalenian people are homo-sapiens from the period of the late upper palaeolithic (24000 to 15000 years ago), found in western Europe. They are typically seen as hunter-gatherers yet are not known to have had strong regional connections. They did not belong to the same community and so may have experienced a variety of different things whilst also acting/behaving in different ways also.

One aspect of the characterisation of these people has been the question of cannibalism. Human remains that have signs of flesh being deliberately removed from the bone and humanly made breaks have been found in caves around western Europe, including in Gough’s Cave (Somerset, England), Le Placard cave (Charente, France) and Isturitz (Girande, France). Figure 1 below shows an example from the natural history museum of the remains found at Gough’s cave. It shows the assembling of the skull cap into vessels that have been interpreted as that which can be drunk from. Scholars suggest that this links to the funerary practices of the upper palaeolithic Magdalenian culture from approximately 15000 years ago. However, it must be noted that this idea generalises a culture and people through three varied and therefore should not fully generalise these people as having cannibalistic funerary practices.

Figure 1: human cranial remains from Gough’s Cave

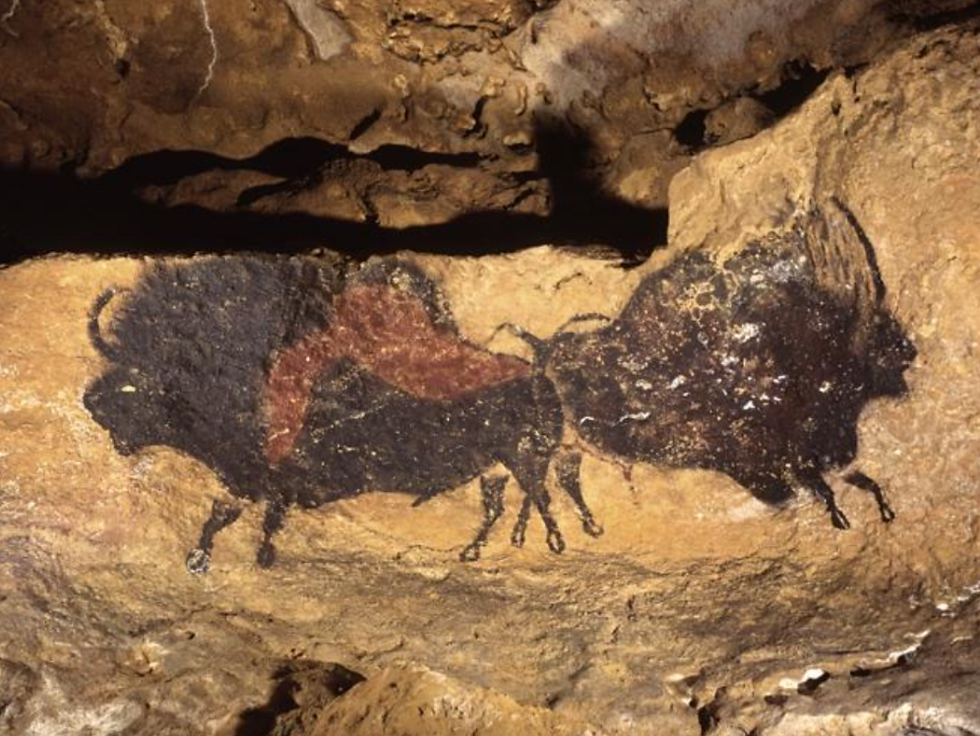

The relief of the caves was given careful attention; the painters noticing how to use the natural features of the cave to aid in their presentation. Obtuse angles that meant the paintings were not entirely vertical meant an ability to emphasise the anatomical shapes of the animals. Not only this but technical ability is evident with Figure 2 showing how two images have been superimposed both with shapes and colour to imitate two bulls moving symmetrically away from each other.

Figure 2: Panel of the crossed Bison in the Nave

The majority of the figures that appear in the cave are that of animals, namely equines, stags, aurochs etc. However, anthropomorphic figures appear in one scene – the shaft scene. This is particularly important, I believe, in understanding the motivations of the Magdalenian or Magdalenians who crafted these scenes. From my point of view (unprofessional as it is) the lack of homo-sapiens suggests the depictions are not about the human point of view – not about the everyday life nor hunt of the community – but rather something greater. It is knowledge of the importance of nature and the cyclical structure of life and regeneration.

The cave art is unique to the period of the Magdalenian and Lascaux cave paintings; the period after this homo-sapiens started to focus their art more on themselves. This change in focus alludes to the sense of a greater connection between nature and human that transformed into something focused on the egoistic lifestyle of homo-sapiens instead. Thus, positing the question: how different would society be if art did not become focused on homo-sapiens and instead remained about nature?

My personal favourite interpretation of the Lascaux cave art is that of Norbert Aujoulat. Aujoulat writes of a cosmogonic interpretation (theory in relation to the creation/origin of the universe) of the equine pigment paintings. Their analysis points out that the physiology of each animal depicted in the Lascaux paintings can be associated with a different season. The equine anatomy corresponds with what these equines would look like in early spring. This is in comparison with the other animals– such as the summer aurochs, and the autumn stags . The seasonal association of each animal suggests that they all relate to, or represent,the passing of time. Each also semiotically denotes the beginning of a period in the mating cycle. Aujoulat therefore suggests that the paintings are representative of the rhythm of life and the regeneration of nature, in effect suggesting that nature is about balance, harmony and renewal. The deeper revelation this denotes is that pre-historic culture viewed the most important things to depict as that of the facets of nature as cyclical, alluding to how the world was seen.

Figure 3: Brush painting of spring equine

Other prehistorians speak of the images as relating to constellations of the taurus/ pre-historic star charts or of mystic rituals. David Lewis Williams stated how the paintings were even a result of visions that were experienced during a trance in ritualistic dancing. These mystical interpretations continue to suggest the other-worldly nature of pre-historic culture, yet do not hold much concrete justification.

Traditionally, the success of the hunt is thought to be the correct interpretation. The art is seen as; a form of visual communication for the community to understand the migration and breeding activities of their prey. At face value this interpretation seems very logical. But this view may become anachronistic when – you look to the Magdalenian diet which consisted mainly of reindeer, who are rarely found in these paintings.

Tragically this historic landmark has been forever altered by its presence in the modern world. Through the scrabble of tourists to look upon the art with their own eyes, the conditions of the paintings quickly diminished. The excess carbon dioxide started to damage the quality and pigment. Therefore, tourists and unapproved visitors are no longer allowed in. But do not fret if you ever wished to see them in person! An adjacent cave was turned in Lascaux II holding identical replicas of the cave art, and there is even a Lascaux III which has become a travelling exhibit.

It would currently be impossible to concretely identify the meaning behind such art as that of the Lascaux caves, but that does not mean we cannot appreciate what it gives us, insight into a sophisticated culture of the (very) distant past, one which is very different from our own.

Comments